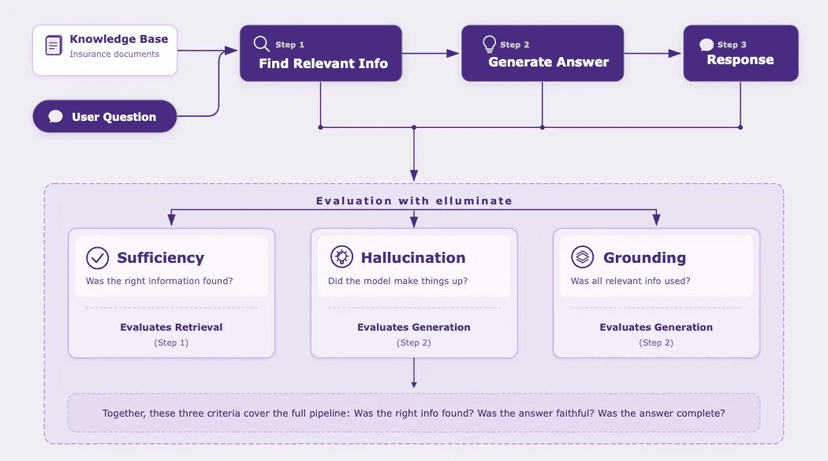

A German health insurance company wanted to add an AI-powered search to their website. Users would ask questions like "Does my plan cover dental cleaning?" and get helpful answers instead of a list of links. The challenge: how do you know the AI is giving correct answers about insurance policies before you ship it to millions of users?

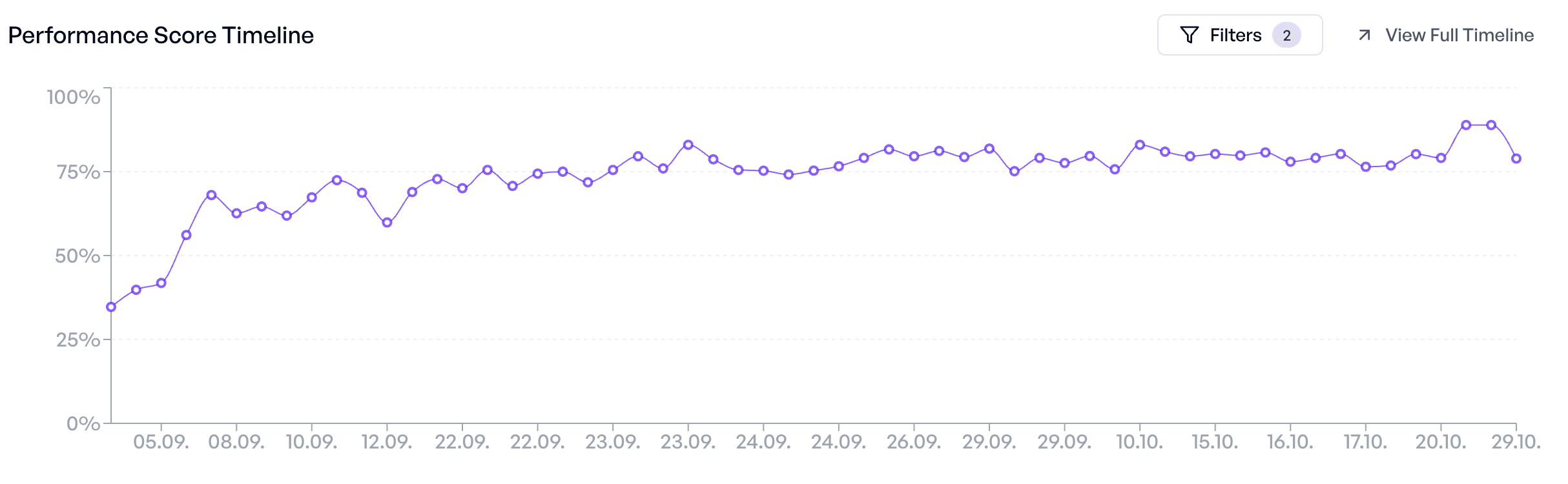

We worked with their team to build a test set of 50 cases, drawn from the most common questions users were already typing into their existing search. Over seven weeks and 57 experiments, we iterated the system from a 35% pass rate to over 80%—even as we kept adding harder cases. By launch, stakeholders could see exactly which questions the AI handled well and which still needed work. The test set made decisions possible.

This post breaks down what we learned. We'll cover how to build a test set that catches failures before users do, how to get useful labels from domain experts without burning them out, and how to keep your test set relevant as your product evolves.

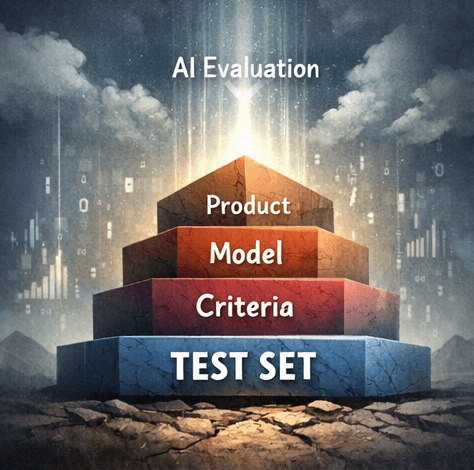

What Is a Test Set?

A test set is a collection of inputs you run your AI against to measure how it performs. Each test case typically includes:

- Input variables: the data you pass to your prompt (a user question, a document, a product description).

- Ground truth labels: what a correct response should contain or do. This is what you evaluate against.

- Metadata: tags like category, difficulty, or source that help you slice results and spot patterns.

For the health insurance project, a test case looked like this:

Query: "Does my insurance cover professional dental cleaning?"

Expected content: Yes, once per year for free at participating dental network practices, or through the bonus program as a health subsidy.

Expected links: /benefits/dental-cleaning

Notice what's not here: a full reference answer. We didn't ask experts to write the perfect response. We asked them to specify the facts that must be present and the links that must be included. This distinction matters—we'll come back to it.

Start with Real User Data

The most important principle: your test cases should come from real usage. Synthetic examples are useful for filling gaps, but nothing beats actual questions from actual users.

For the insurance search, we pulled the top 50 queries from their existing website search logs. These weren't hypothetical—they were the questions users typed most often. This gave us immediate confidence that we were testing what mattered.

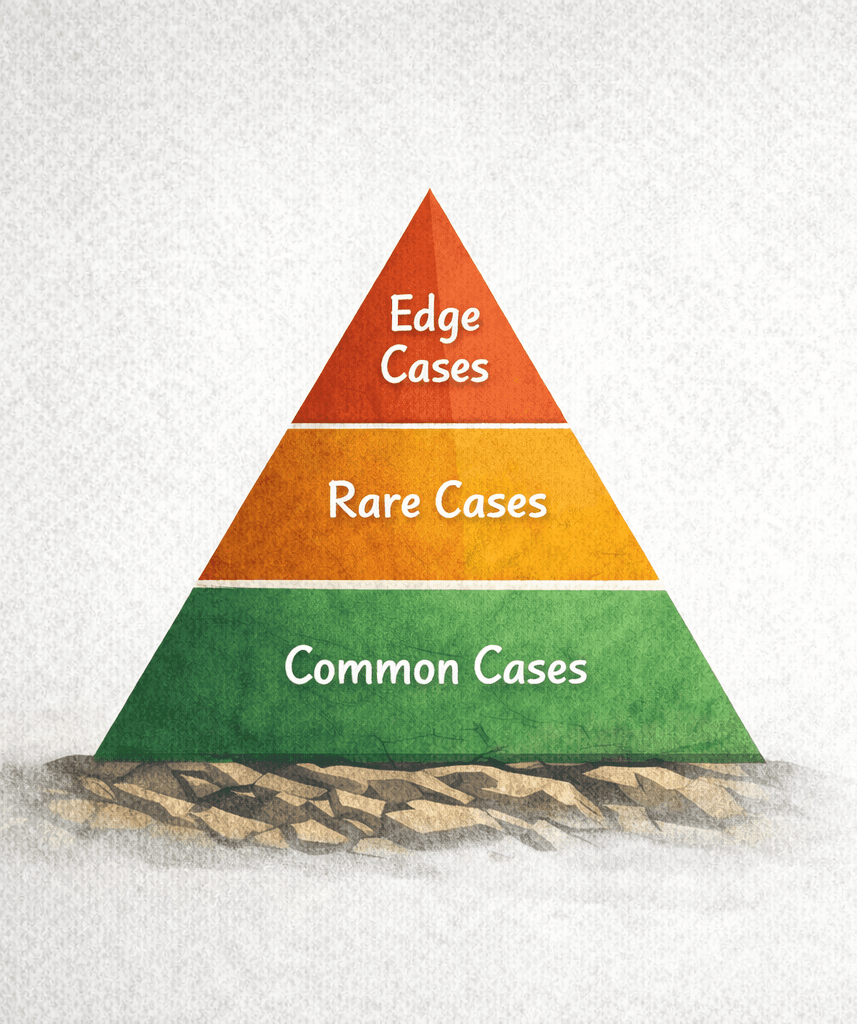

Your test set should cover:

- Common cases: the everyday questions that make up most of your traffic. If you get these wrong, users will notice fast.

- Variations in phrasing: users ask the same thing many ways. "What's the customer service number?", "how do I contact support", "phone number please", "CALL YOU???"—your AI needs to handle all of them.

- Rare but valid cases: unusual scenarios that still need to work. For insurance, this might be questions about obscure policy details or edge cases in coverage.

If you don't have production data yet, start with what you have: customer support tickets, sales call transcripts, or questions from user interviews. The goal is to ground your test set in reality, not imagination.

Target Specific Failure Modes

General test sets tell you if something is broken. Targeted test sets tell you exactly what.

During the insurance project, we discovered a frustrating pattern: the AI would correctly answer questions about phone numbers—but the domain experts didn't want that. They wanted the AI to direct users to the contact form instead, because form submissions get resolved faster than phone calls.

The model kept ignoring this instruction. It would dutifully provide the phone number even after we added guidance to the prompt. To fix it, we created a small, targeted collection: 8 different ways users ask for phone numbers. "What's your phone number?", "How can I call you?", "I need to speak to someone", "customer service hotline", and so on.

This mini test set let us iterate quickly on just that behavior. We could run experiments in seconds instead of minutes, trying different prompt phrasings and few-shot examples until we got reliable compliance. Once it worked, we moved two representative cases into the main collection for regression testing.

The pattern: when you find a category of failures, create a focused collection of 5-10 targeted cases. Use it to iterate fast. Then graduate a few cases to your main collection once the issue is solved.

Edge cases to look for include malformed input (typos, mixed languages, missing punctuation), adversarial input (prompt injection attempts, nonsensical requests), boundary conditions (very long or short inputs, empty fields), and ambiguous cases where the right answer isn't obvious.

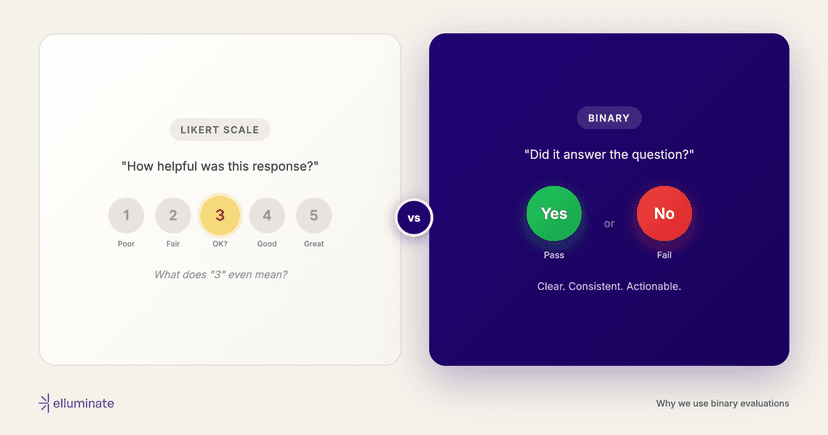

Labels That Don't Burn Out Your Experts

Here's where most teams go wrong: they ask domain experts to write complete reference answers for every test case. This is slow, painful, and often counterproductive. Experts burn out. Answers get inconsistent. And exact-match evaluation is fragile anyway—there are many ways to say the same thing correctly.

Instead, ask experts to specify the minimum requirements: what facts must be present and what links must be included. This is faster to write, easier to verify, and more robust to evaluate.

For the insurance project:

- We generated draft labels using a strong model (too expensive for production, but good for bootstrapping).

- Domain experts reviewed and corrected these drafts, adding their own knowledge about what must be mentioned.

- 5 experts spent about 1 hour each labeling 10 cases—roughly 5 hours total for the initial 50-case set.

The experts were relieved. They didn't have to craft perfect prose. They just had to say: "For this question, the response must mention X and Y, and link to page Z." That's something they could do quickly and confidently.

Example—simple but clear guidance:

Query: "What's the customer service phone number?"

Expected content: Should reference the contact form as the primary option.

Expected links: /contact/form

This format also makes evaluation criteria straightforward. You can write criteria like: "Does the response include the expected facts?" and "Does the response link to the expected pages?" These are binary, unambiguous, and reusable across your entire test set.

An example criterion referencing ground truth:

Does the response cover the required information? Required: {{expected_content}}

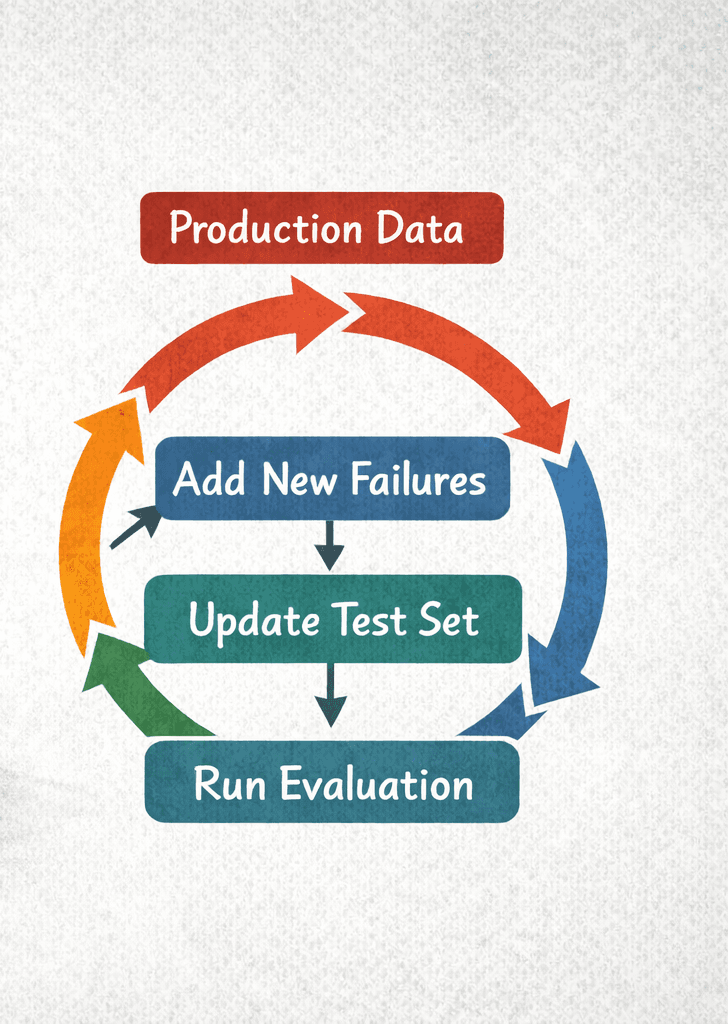

Treat Your Test Set as a Living Document

A test set isn't something you build once and forget. It evolves with your product.

Throughout the insurance project, we kept the collection live. When we noticed labeling mistakes, we fixed them. When underlying data changed (a policy updated, a page moved), we updated the expected content. When user testing revealed gaps—questions we hadn't anticipated—we added them.

We started with 50 cases and reached 80 by launch. The test set grew not through arbitrary expansion, but through discovered need.

When to update your test set:

- After any production incident: if users hit a failure, add that case. You shouldn't see the same bug twice.

- When you change your prompt significantly: new behaviors need new tests.

- When underlying data changes: if your knowledge base updates, your labels might be stale.

- When you notice patterns in failures: clusters of similar errors suggest you need more coverage in that area.

After public deployment, we continued adding cases from production usage. Interesting failures became test cases. The test set kept growing more representative over time.

A Practical Workflow

Here's the process that worked for the insurance project—and that we've seen work across many teams:

- Pull real queries: Start with 30-50 examples from production logs, support tickets, or user research. These are your foundation.

- Generate draft labels: Use a strong model to produce initial ground truth. This isn't your final answer—it's a starting point for experts.

- Expert review: Have domain experts spend 1-2 hours each correcting and enriching the labels. Ask for facts and links, not full prose.

- Run your first experiment: See where you stand. Look for patterns in failures. Are certain categories broken? Certain phrasings?

- Create targeted mini-sets: For stubborn failure modes, build small focused collections of 5-10 cases. Iterate fast. Graduate winners to the main set.

- Keep it live: Update labels when data changes. Add cases when you find gaps. Remove cases that are no longer relevant.

Common Mistakes

- Testing only happy paths: if every test case is a well-formed, common question, you're not testing—you're confirming your hopes.

- Too few cases: 10-20 cases don't give you statistical confidence. Start with at least 50.

- Too many cases: more than 150-200 becomes hard to maintain. If you're there, consider splitting into focused collections.

- Asking experts to write full answers: this burns them out and produces inconsistent labels. Ask for facts and links instead.

- Static test sets: a test set you built six months ago and never touched is lying to you. Keep it current.

- Ignoring production data: synthetic examples are useful supplements, but real user queries are irreplaceable.

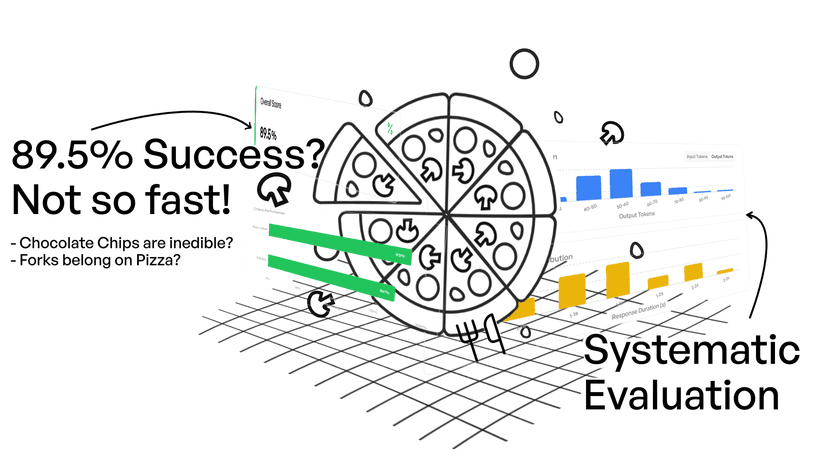

The Payoff

Over seven weeks, the insurance team ran 57 experiments—20 prompt versions, 10 system changes, multiple model comparisons. Each experiment took minutes to run and gave clear results. The pass rate climbed from 35% to over 80%, even as we added harder cases.

More importantly, the test set made decisions possible. When stakeholders asked "Is this ready to ship?", we could show them exactly which questions worked and which didn't. We could quantify risk. We could prioritize fixes. The test set turned "I think it's good" into "Here's what we know."

After launch, the test set kept paying dividends. Production failures became test cases. The system kept improving. The initial investment of 5 hours of expert time has been reused across dozens of experiments and will continue to be used as long as the product exists.

That's what a good test set does: it compounds. Build it right once, keep it current, and it becomes the foundation for every improvement you make.

We work directly with teams to design test sets and evaluation workflows for their specific use cases. If you're building AI and want to ship with confidence, let's talk.

Schedule a Demo